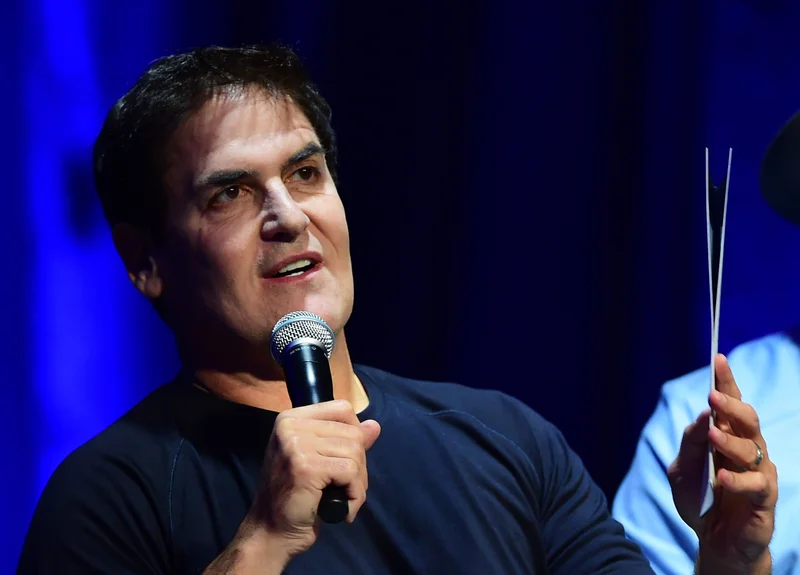

Every so often, an idea pops up on the internet that isn’t just a hot take; it’s a system-level schematic disguised as a social media post. When I saw Mark Cuban’s post on X calling for a radical rethinking of employee compensation, I honestly just leaned back in my chair. This wasn't just another billionaire from Shark Tank talking about wealth. This was an engineer, a systems thinker who built his fortune on understanding how networks function, proposing a new design for the most complex network of all: the modern corporation.

The proposal, sparked by a recent Oxfam report on ballooning billionaire wealth, is deceptively simple. Cuban suggests that companies should be incentivized to give all employees shares at the same percentage of their cash earnings as their CEO. He’s suggesting a kind of algorithmic fairness in ownership. In simpler terms, if a CEO’s total compensation package is made up of 1% stock, then every single employee’s compensation package—from the front-desk receptionist to the senior VP—should also be made up of 1% stock.

This is the kind of breakthrough thinking that reminds me why I got into this field in the first place. It’s not a call for handouts or a political attack on success. It’s a beautifully elegant piece of social engineering. It’s a proposal to rewrite the source code of corporate culture. What happens when you turn every employee, regardless of their role, into a genuine owner? What happens when the person cleaning the floors at night has a vested, tangible interest in the company’s stock price? You don’t just get a cleaner floor; you get a stakeholder.

A New Operating System for Capitalism

For decades, we’ve been running our economy on an outdated operating system. Let’s call it "Shareholder Primacy 1.0." It was designed with a single, primary function: maximize returns for external investors. And it worked, for a time. But like any old code, it’s developed bugs. The Oxfam report, noting a $33 trillion increase in billionaire wealth since 2015, is essentially a bug report on a massive scale. The system is creating runaway feedback loops that concentrate wealth in a way that is not just socially questionable but, I would argue, economically inefficient.

Cuban’s idea is like a major software patch. It’s an upgrade to "Stakeholder Capitalism 2.0." It doesn't throw out the old system; it rewires it from within to be more robust, more resilient, and more powerful. By pegging employee stock grants to the CEO’s, it creates an unbreakable link between the fortunes of the boardroom and the factory floor. Imagine a world where the janitor, the coder, the salesperson, and the CEO are all pulling in the same direction not just because of a paycheck but because their personal wealth is directly tied to the company's success—that's a feedback loop that could unleash a level of productivity and innovation we haven't seen since the dawn of the internet.

This isn't some utopian fantasy. We’re already seeing the green shoots of this thinking. Mark Cuban called for workers to get a slice of their employers’ $33 trillion success—now, Samsung is awarding shares to staff for the first time. This isn't charity. It’s a strategic move by one of the world’s largest tech companies to foster loyalty, drive innovation, and align incentives across a massive, global workforce. Cuban, who has a track record of disrupting industries from sports with the `Dallas Mavericks` to pharmaceuticals with his `Cost Plus Drugs` company, is simply articulating the next logical step. How do we turn this from a one-off program into a fundamental principle of our economy?

From Abstract Code to Human Impact

Let's bring this down from the 30,000-foot view. What does this actually feel like for the people inside these companies? The current model often creates a quiet, simmering resentment. Employees see reports of record profits and staggering executive bonuses while their own wages barely keep pace with inflation. It creates a transactional relationship: you give me labor, I give you cash. The result is disengagement, quiet quitting, and a workforce that feels more like a collection of mercenaries than a unified team.

Now, picture the alternative. An engineer finds a way to save the company $1 million a year by optimizing a manufacturing process. In the old system, she might get a small bonus and a pat on the back. In Cuban’s proposed system, that $1 million in savings directly contributes to the company's profitability and, by extension, its stock price—a stock she now owns a piece of. Her ingenuity is no longer just benefiting a distant, faceless shareholder; it’s directly benefiting her, her colleagues, and her family.

This transforms the very nature of work. It’s the difference between being a renter and being an owner. When you rent an apartment, you might report a leaky faucet. When you own the house, you fix it, you improve it, you invest in it. What happens to innovation when the person on the assembly line has a vested interest in making the product better? What happens to customer service when the support agent’s retirement depends on the company’s reputation? How does a company's entire culture shift when the artificial line between "labor" and "capital" begins to dissolve?

Of course, this isn't a silver bullet. The implementation would be incredibly complex. How would it apply to private companies or early-stage startups where equity is already a core part of compensation but cash flow is tight? What regulations would be needed to prevent exploitation? These are serious questions that require serious thought. But pointing out the difficulty of building a rocket ship isn't a valid argument against going to the moon. The core principle—that those who create the value should share in the value they create—is too powerful to ignore.

This Is What Re-Engineering the Future Looks Like

Mark Cuban didn't just tweet a financial proposal. He sketched out a new social contract for the 21st century. It’s not about taking from the rich and giving to the poor; it’s about creating a system where the process of getting rich is inherently more inclusive. It leverages the engine of capitalism—the stock market, which Cuban correctly identifies as the source of this wealth explosion—and makes it accessible to everyone who powers it. This is a profoundly optimistic and, frankly, a more intelligent form of capitalism. It recognizes that a company’s greatest asset isn’t its patents or its real estate; it’s the collective creative energy of its people. And the smartest thing you can possibly do is give every single one of them a reason to invest that energy as if the company were their own. Because, in this model, it would be.