Of all the challenges we face in the 21st century—from climate change to artificial intelligence—I never thought the most insidious would be paperwork. But as I look at what’s unfolding in the American South, I see a quiet catastrophe being engineered not by malice, but by a profound failure of design. A storm is gathering over places like East Carroll Parish, Louisiana, a small town that’s already seen its best days fade into memory. And this storm isn't an act of God; it's a hurricane of bureaucracy, built by us.

Richard Roberson, who runs the Mississippi Hospital Association, put it best: "We know there's a hurricane out in the Gulf... We don't know exactly what the category of the storm is going to be at landfall. But we know we need to be prepared for it."

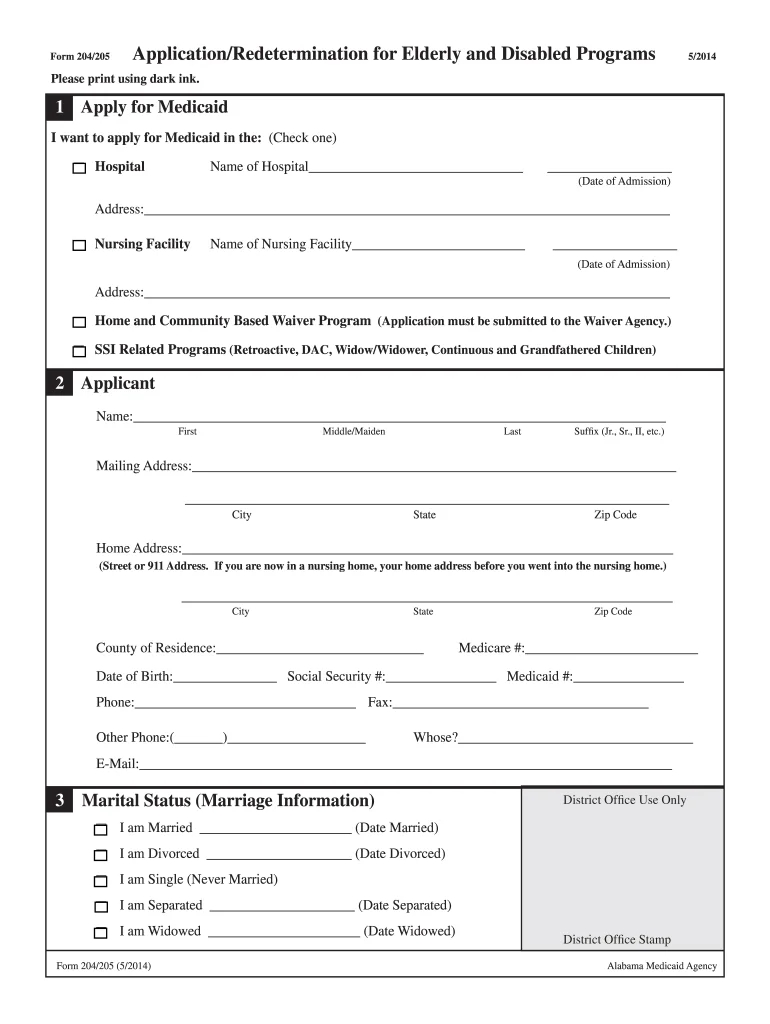

He's talking about the nearly $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid scheduled over the next decade, a result of a new federal law. But the real story, the one that should keep every systems thinker and innovator up at night, isn't the money. It's the method. The law introduces a set of bureaucratic hurdles—work reporting requirements, semi-annual eligibility checks—that are poised to knock millions of people out of the healthcare system. When I first read about the predictable outcome of these policies, I honestly just sat back in my chair, speechless. We are watching a slow-motion, man-made disaster, and we're the ones who designed the blueprints.

The Ghost in the Machine

Let's be incredibly clear about what’s happening here. The new law will require adults on expanded Medicaid to prove they are working, volunteering, or going to school for 80 hours a month. On the surface, it sounds like a policy debate. But it’s not. It’s a systems problem. Why? Because the data is already in: the overwhelming majority of Medicaid recipients are already working, often in multiple low-wage jobs.

This isn’t a theory. We have the case study. When Arkansas implemented a similar system in 2018, nearly 18,000 people were kicked off their health insurance in less than a year. And the kicker? There was no evidence it had any positive impact on employment. People lost coverage not because they weren't working, but because they got lost in the paperwork. They fell victim to what experts call procedural disenrollment—in simpler terms, they were defeated by red tape. Experts worry more paperwork will deter Medicaid recipients.

What does that look like on the ground? It looks like Sherila Ervin, a 58-year-old who has worked in a school cafeteria for 25 years, worrying that a single mistake will cost her the high blood pressure medication she relies on. It looks like Nevada Qualls, a 25-year-old mother of two working as a cashier, who rightly calls the new requirements "another thing to add to my load that is already heavy." In the rural South where Medicaid has been a lifeline, residents brace for cuts.

These aren't people looking for a handout. They are people who are already working, already contributing, who will now be forced to navigate a labyrinth designed to make them fail. It's like we've built a system that demands you prove the sun rises every morning by filling out a complex form, in triplicate, with a pen that’s always running out of ink. The task itself is simple, but the process is engineered for failure. Is this really the best system we can imagine?

A System Intentionally Designed for Friction

This is the kind of breakthrough that reminds me why I got into this field in the first place—to solve complex problems, not create them. Yet here we are, on the verge of forcing states like Louisiana to build massive, clunky, and expensive IT systems by 2027 to track millions of people, a system that has to connect to countless employers and verify hours for people working multiple part-time jobs with variable schedules—it’s a data integration nightmare that would give a team at Google pause, and we're asking underfunded state agencies to build it on a shoestring budget and a prayer.

The hope, according to advocates, is that Louisiana will engage with communities to "mitigate as much harm as possible." But what does it say about us when the goal of a new system isn't to help, but to simply "mitigate harm"? We are leveling this bureaucratic weight on the very people who can least afford to bear it, and for what? To solve a problem—unemployment among Medicaid recipients—that largely doesn't exist.

This brings us to the moment of ethical consideration we can no longer ignore. As builders, as innovators, as thinkers, what is our responsibility? Are we creating tools that empower people, or are we designing digital cages? A pilot program for these requirements in Louisiana saw a response rate of just 7%. A 93% failure rate isn't a glitch; it's a feature. It’s the quiet, intended outcome of a system that values bureaucratic tidiness over human life.

We've seen what happens when people get a foothold. In East Carroll Parish, Medicaid expansion slashed the uninsured rate among working-age adults from nearly 35% down to under 13%. People got care they desperately needed. As nurse Jennifer Newton, who works at the local clinic, asks, "We've made so much progress. Why are we going back?"

We Can Build a Better Storm Shelter

This isn't a political problem; it's a design challenge. And design challenges have solutions. We live in an age where we can instantly verify identities, transfer funds across the globe, and automate incredibly complex logistical chains. We have the technology to build systems that are seamless, empathetic, and human-centered. We could build a system that automatically verifies employment through state tax data, that sends simple, clear mobile alerts, that offers help instead of threats.

The obstacle isn't a lack of technological capability. It's a lack of imagination and political will.

So, the hurricane is coming. We can see it on the radar. But we don't have to just brace for impact. We can build a better storm shelter. This is a call to action for every designer, engineer, and policy maker who believes technology should serve humanity, not ensnare it. Let's stop building systems designed to fail people and start building systems that help them succeed. The blueprints are in our hands.